Part of doing a trademark application is to ensure they are not applying for something that is bound to fail. With respect to word marks in particular, is fairly easy to do a search first four names that a trademark examiner might find to be “confusingly similar”. If a previously registered trademark has a name that the examiner considers to be “confusingly similar”, then in all likelihood it’s going to be difficult or impossible to register your desired mark. Graphic marks are a different beast, and are a little bit more difficult to search for. So this blog post is just about searching for word marks in the Trademark Electronic Search System (TESS).

Here’s the steps that I usually take to do a search:

- Do a quick-and-dirty search to ensure that there are no direct-hit registrations that will clearly block the registration.

- Make a list of the trademark classes that might be relevant.

- Make a list of search terms: The whole mark you might apply for, constituent parts of the mark, and synonyms for parts or the whole.

- Construct searches in TESS using the list of terms you created, limited by the classes you found.

Let’s go through each one of those. For purposes of this post, I am going to imagine a hypothetical client that wants to use the name BANANA CONSULTING for a company that provides technology and management consulting services – sort of like a CTO for hire.

Do a Quick and Dirty Search

I usually start with the easiest searches to see if there are any really obvious problems with the proposed mark. After that, I move to the more complicated searches in order to look for more tangentially conflicting marks.

The most obvious thing to do is go to

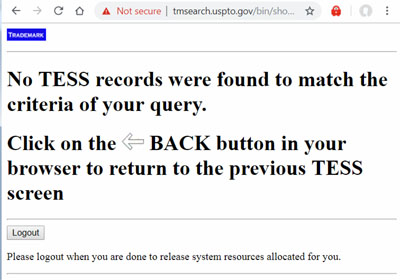

http://tmsearch.uspto.gov, click “basic search”, and type in BANANA CONSULTING. No hits! Yay!

However, that just means that there are no registrations for marks that literally match the entire string “banana consulting”. What about banana by itself? Because the word “consulting” just describes the services, “banana” is really the key word in this trademark. And you could imagine a company just called “banana” that offers consulting services that would be confusingly similar with “banana consulting”. So we are not done. We’ve just done the quickest search to avoid extremely obvious conflicts. Typing just “banana” into TESS basic search is not so helpful:

1696 records! I don’t have time for that. How can we filter these to get fewer results we have to review one by one?

Limiting A Trademark By Goods and Services Keyword

The first way to limit is by words that appear in the goods and services description. Since all of the services my hypothetical client wants relate to “consulting” in some way, that seems like the obvious keyword to use.

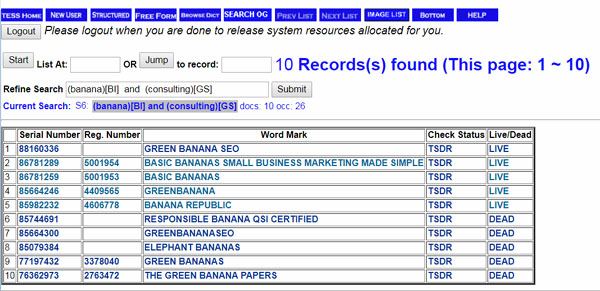

For this, we are going to use the TESS “structured search”. Go back to [insert URL] and click “structured search”. This gives you a form where you can enter two different search terms, limited by field in the USPTO database. In the first one, I enter “banana”, with a field of “Basic Index (Combined MP+PM+MN)”. The Basic Indexes basically all of the English words in the mark. In the second, I’m putting “consulting”, And choose the field as “Goods & Services”. You then have to choose “AND” instead of “OR” in the drop down to the right. If you leave it at the default “OR” you will get tens of thousands of results again.

We can see that there are four live registrations, and one not-yet-registered application, for banana-related marks that have consulting-related services. The ones that have a registration number are registered. And then the other important column is “live/dead”; both can be important, but really the live ones are what we’d look at first.

At this point are doing a search for an actual client I would probably review the four live registrations and live application and report back to the client. I haven’t looked at all four of those super-carefully and that certain legal analysis involves judgments and interpretation gray area . . . but probably it isn’t looking super-good. However, since this is a blog post that is meant to be instructive, I’ll keep going with a more detailed search to see if we can find any other possibly-conflicting marks. But first, what about those dead registrations and applications?

Do you need to worry about dead trademark registrations and applications?

These are sort of like when Indiana Jones comes across a dead body in a cave: not a direct threat, but you want to make sure that whatever got them isn’t going to get you also. For that reason, I will usually look to very similar marks in TSDR are to see what killed them. For registrations, most often this is just because they expired and the owner didn’t renew them. For applications, sometimes they are intent-to-use and just never got completed.

But if there was an office action on a dead mark, especially if it is very similar to the one you’re considering applying for, it’s a good idea to skim it to see what the reasons were. Often it will be for similarity to an existing registration, and so You’d want to type that registration number into TSDR to see if it is still alive. Likewise, office actions and other dead applications can be informative regarding descriptiveness if the mark in question might be considered to be descriptive of the goods or services.

Limiting A Trademark Search By Class

Previously researched using “consulting” as a keyword. But what about other similar services that might not use that word? The other way to search goods and services is by classification.

Trademark classes are broad categories of types of goods or services that the USPTO uses in order to make the whole process of trademark registration more manageable. The class itself does not give any additional rights, ((TMEP 1401.01 and 55 USC 1112)) because what really counts is the description of the goods and services. However, since the classification system exists for administrative convenience for the USPTO, so you might as well use it for your own administrative convenience as well when your search.

First, create a list of the possible trademark classes.

I know of three methods to search for class numbers based upon a general sense of what goods or services are involved:

(1) Look through the Nice Treaty remarks and headings. These are the formal summaries of the trademark classes used by the USPTO. It’s pretty lengthy to read through directly. Instead, I would usually search within the webpage for specific keywords. In this case, searching for “Consult” gives some Information – there is a note that Business consultancy is class 35. often I just use the Nice Treaty remarks and headings to look up more detail about a classification that I have found through one of the other two methods below.

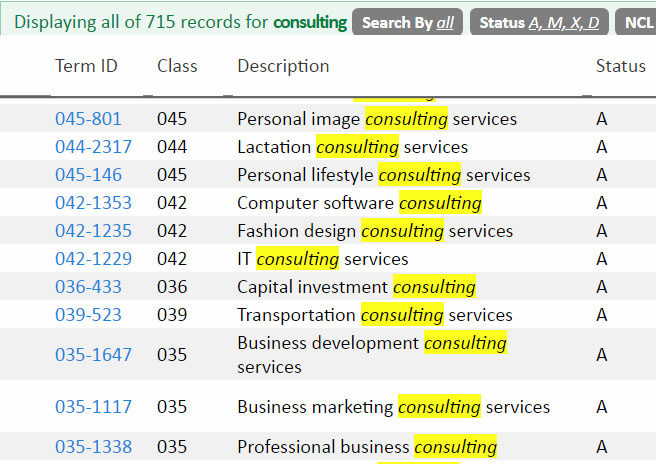

(2) Use the ID Manual, which is a USPTO database of pre-approved goods and services descriptions, along with the class that they are in. Typing in consulting here is pretty informative because it gives a reasonably-sized list of descriptions that have the word “consulting” in them. For relatively straightforward types of business like my CTO-for-hire example, this is probably sufficient. Assuming the role is sufficiently oriented towards both business and technical matters, my client would probably apply in classes 35 for business consulting, but also class 42 which is for technical and scientific services.

(3) See what classes your competitors used in their applications. If you are a large company with a massive legal budget, typically you will apply in every conceivable class. So by searching for a big company that has similar services, you can get a sense of the universe of possible classes to apply for. The only problem can be that sometimes the massive legal budget leads to such an exhaustive trademark application strategies that it’s hard to find one for just the core services. But, for example, if I do a basic TESS search for COGNIZANT, a giant IT consulting firm, then I get 62 trademark applications. The core marks are usually going to be the ones that the company applied for first, which are going to be the last ones in the TEST search results. In this case, I can see that Cognizant applied in class 42 first, and then shortly afterward did another in 16, 35, 36, and 42. Two of those confirm what I already found with the previous search; I might then take the other two – 16 and 36 – and review the Nice Treaty descriptions in order to see if they might be “confusingly similar” to my client’s business.

Second, search for related marks in those classes

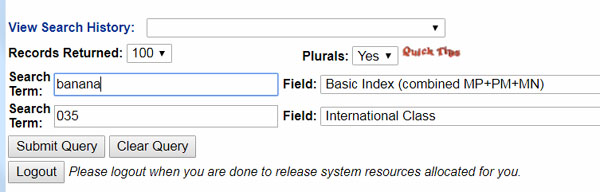

I still use the structured search when I need to formulate a more complex query. So in this case I start with the name and the basic index again, and insert one of the classes I’m searching for in a field searching for the “International Class”.

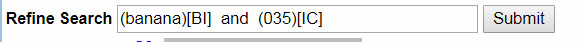

This gives a rather surprising 92 results. Apparently there are a lot of business services that involve bananas. However, we also want to search for a piece one other class that we found above: 42. In the results screen, you can see where the structured searches is converted into a sort of pseudo-code for querying the database:

Changing that search string can provide a quick way in order to modify your search. If you want to remove all of the “dead” applications/registrations, you can add: and (live)[LD]. To switch to another class, you can just change the number from 035 to 042. For whatever reason, all of the international classes have to be submitted as a three digit number with leading zeros.

Analyzing the Results

Looking to the search results can be very easy for by a mark that is arbitrary or fanciful in the trademark strength scale. It can be rather difficult when term start to become more descriptive and it is used in many trademarks for the goods or services. In this case, even though I chose an arbitrary example – bananas usually don’t have anything to do with consulting – because of the apparent popularity of bananas, I would still have at least several dozen trademark registrations to review and analyze for possible risk of conflict with my client’s application.

describing what that analysis is for each mark is beyond the scope of this blog post. This post is mostly about finding the universe of trademark applications and registrations that might be a possible conflict with the desired application. However, as a brief overview, the general process is to compare the desired combination of mark and services with the one that has been applied for our registered already. If they are so similar that a reasonable consumer would consider them “confusingly similar”, then an examiner might issue an office action rejecting the application.

Searching for Variations of the Mark

Because the test for comparing trademarks is a “fuzzy” one of confusing similarity, it is not sufficient to just do a search for the mark that you want. You also have to do a search for marks that might be confusingly similar. That usually means common misspellings, and variations on the word. It might be impossible to actually get all of them, but it is a good idea to search for the ones that come to mind, and to do wildcard searches.

For spelling variations, you’re just doing the three types of searches outlined above, but substituting spelling variations for the actual spelling of your mark. the USPTO has helped you with this a little bit; when the mark clearly refers to an English word but is slightly varied then USPTO staff and are what is called a “pseudo-mark”. For example, one of the results that I found was for an application for “hibanana”, and the USPTO entered pseudo-marks for “high banana” and “high banana”.

To do wildcard searches use a question mark to replace a single character, or and asterisk (*) to represent zero or more characters at the beginning, end, or middle of your search term. so in my example, I might do additional searches for *banana* with the class limiters in order to see if other applications and trademarks that are based on the word banana but have extra stuff added on to the beginning of the end. Most likely many of those would be caught by the pseudo-marks anyway if I were just searching for “banana” by itself, but it’s a good way to double check.

Got Questions?

This is meant as an overview of searching techniques using TESS, but does not cover every scenario and does not constitute legal advice. If you’d like to have an attorney do your search, you might look at my flat-fee trademark application service (which includes a search), and also my legal checklist for naming a business. If you’re interested in talking about your trademark needs, to see if we might be a good attorney-client fit, then please contact me.