In a negotiation, there are times to talk, and times to be quiet and listen — or to just enjoy the silence.

When to talk. There is a certain value to rationalizing your demands. If you just leave it as a simple demand, the counterparty may think, “Forget this, we can find someone else who will do this without limiting their liability.” But if you rationalize it, a counterparty will often feel morally compelled to up the ante and respond with a better justification; or if they can’t, to give the point up. Say for example that you are a software developer and demand a contract should include a limitation of liability clause. It might go like this:

Potential Client: “We have to remove this limitation of liability clause.”

Developer: “We provide these services to many customers, and we have to avoid the situation where an liability from one customer wipes out the company.”

Potential Client: “But doesn’t your company stand behind the software that you write?”

Developer: “We do provide first rate customer service, seven days a week. But a large company like yours could incur such large damages as to put us out of business. We also can’t provide the services at this low cost if we included liability protection. Essentially our business model is software, not insurance.”

There may be another riposte from the “Potential Client” side. The larger point, though, is that these fencing matches of rationales sometimes do matter. Whereas the BATNA is more a matter of hard economics, this seems to be more a matter of psychology: sometimes people give up on points rather than continuing to struggle with coming up with a better counter-reasoning. This is especially true with smaller points that both parties seem to recognize as too small to walk away on.

There may be another riposte from the “Potential Client” side. The larger point, though, is that these fencing matches of rationales sometimes do matter. Whereas the BATNA is more a matter of hard economics, this seems to be more a matter of psychology: sometimes people give up on points rather than continuing to struggle with coming up with a better counter-reasoning. This is especially true with smaller points that both parties seem to recognize as too small to walk away on.

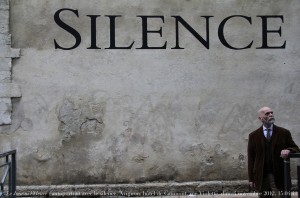

The Value of Silence. Once you’ve laid out your reasoning, though, don’t feel like you need to keep talking about it. Many people find silence in a conversation to be really uncomfortable. Especially if you have just made a request and provided a reasoning for it, give it a quiet moment. This enforces the psychological need of the other party to give a counter-reasoning. If they can’t think of a counter-reason, and are uncomfortable with silence, then sometimes you will just get a concession to make the problem go away.

The other value of silence is that the other party may actually have a valid point, or there may be a disconnect between what you think they think, and what they are actually thinking. It may be that in hearing the other party’s reasoning, there may be a compromise to be made.

“Autoportrait avec le silence” by Renaud Camus, used under cc-by, source.